Lessons from Remodeling

Remodeling my house is one of the biggest, scariest, and most expensive things I've ever done. I made a lot of costly mistakes that I'm going to share here. Hopefully someone (myself included) can learn from them.

Project Description

I live in a 2-story, single-family house in San Francisco. Built in 1924, this place is pretty old but was maintained really well. In fact, it was in great shape right up until it went on the market. The last owner tried to prep it for sale by hiring cheap painters and carpenters. Despite 80 years of careful maintenance, we lost a lot of nice detail.

That said, it wasn't exactly a charmer. The house was last renovated in 1956, and even then it was pretty light work. Most fixtures, the bathroom, and the kitchen were all original. That won't do at all.

Lessons Learned

I couldn't begin to write out all the things I learned as part of this process. So many little lessons along the way, and even the ones I include here in this post have days or weeks of agony behind them.

Summary

- Know what you want. Know your priorities.

- Get an architect/designer and have a plan.

- Your team is only as good as the plan.

- The contract is everything.

- Monitor accountability.

- Humans are bad at estimating.

- Never ever live on site.

- Take photos every time you're on site.

Priorities

I'll admit, this was trickier than I thought it would be. There were many instances where we had to make quality, speed, and price trade-offs that we may not have been psychologically prepared for.

Before engaging in any project of this magnitude it's important to know your expectations and have a vision for where you expect the project to finish at. As the person at the top, that's what folks will be looking to you for. At worst, you need to have this in your head and stick to it. At best, you'll help your team see that vision and they can act effectively on your behalf.

Know what you want.

Have A (Specific) Plan

We all know the slogans.

If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.

Well begun is half-way done.

A goal without a plan is just a wish.

That's great and all, but nothing compares to a specific plan. Especially when you're trying to coordinate between an architect, a contractor, their foreman, their sub-contractors, the city, the bank, and everyone else who has a say in what you're doing.

In our case, we had an architect prepare a set of drawings and help us get those approved by the city. That was a huge victory in a town that's world-famous for being impossible to make even interior-only changes! Unfortunately, the designs were almost comically non-specific about what's actually supposed to get built.

It had layouts for where the bathrooms would be, and what the kitchen should look like, and which way doors would swing. But that's not nearly the level of detail you need when the work actually begins.

Let me give you a specific example. In order to install a light switch, someone will need to decide:

- What color and style the switch will be.

- What technical requirements there are for the switch (e.g. amperage, 3-way configuration, etc).

- How high off the ground it will be and how far in from the doorway.

- Which lights or plugs it will control.

- Who should order it and who is responsible for it before it's installed.

That's all stuff someone might look to you (or your plans) for, totally agnostic of actually having the carpenter and electrician get the darn thing installed.

Now multiply that times all of the light switches, electrical outlets, plumbing fixtures, tile, cabinets, base-boards, and other little bits that go into a project and you'll have the scope of complexity at work during a large-scale project like this.

Your team will only be as good as this plan.

One of the early warning signs I saw during this project was that my bids from prospective contractors were different by as much as 50%. That's a huge margin.

It should have been a big red flag that bids to do the work were so wildly different.

If your bids aren't at least close-ish together, it means the contractors aren't all seeing the same project. That's bad, and means their execution could be wildly different from one another.

The Contract Is Everything

When you start your project, you need to think of as many contingencies as you can and make sure there's something in the contract in case that very situation comes up. Most notable delays, change orders, damage to materials, poor installation, and problems discovered well after the project is complete.

Assuming you've gotten all the details out of the way with a clear architectural plan, the question becomes what responsibilities your contractor has to make sure the project gets delivered. In a sense, your architectural plans are the first part of setting the stage for a successful remodel. They're the recipe for what's going to get made. The second part is the contract that describes how you expect that project to get executed.

I made a big mistake here in that I had no recourse after the project. My contractor made some severe mistakes along the way that I didn't notice until the rainy season. By then, it's impossible to get him and his crew back out to fix it.

Monitor & Ensure Accountability

Make sure you know what's happening by setting up some kind of update cadence. Even a twice-per-week check-up on how things are going can go a long way, and make sure it's known up front (maybe even in the contract) what kinds of information you expect to know during these check-ups.

Don't be made to feel guilty for setting a tight communications loop.

- How far along in the project are we?

- How much budget have we used so far?

- What's coming up this week? Next week?

- Are we on track to deliver those things?

- What decisions do you need from me to make the next 2 weeks go smoothly?

Another big question that came up was "who is responsible for this aspect of the project?" That question got muddied when I brought in other sub-contractors myself after the ones my contractor selected didn't work out. This was a mistake because once we started running into problems in the project, there was a lot of finger-pointing.

Having more than one accountable-party on your team will lead to finger-pointing.

For example, I was out of the house Friday while the painter and the plumber were working on-site. When I came home, there was a large puddle of water on the brand new floors. This laminate hardwood flooring isn't supposed to collect water like that because it can lead to warping and peeling. When I confronted both parties, each one said they had no idea where that water came from.

The painter said the plumber was working upstairs and must not have set up a proper catch when they removed some piping.

The plumber said the painter must have left some water on...somewhere.

So now I have to sleuth it out. After seeing a doorframe warp itself shut under the upstairs bathroom, I determined it was the plumber who had done sloppy work, but- ultimately- we needed to have a clearer separation of work so it would be clearer who was the offender.

Which brings me a tangential point...

Work from top to bottom, outside to inside if at all possible.

Gravity is a harsh law that threatens pretty much everything you do. Hardware gets dropped on your new floors and creates dings while day laborers bringing barrows of dirt through the house will ding up the new doors.

As much as possible try to get the big/dirty jobs done first before you do finishes and fixtures.

Humans are bad at estimating

I can almost certainly tell you your project will over-run your budget and your schedule. Shipments get delayed, delivered product doesn't work, a sub-contractor gets sick, or it's Thanksgiving and you get to pay for everyone's vacation days. There's no way around it; you're going to get gummed up in minutia and it'll hit your time/money estimates.

As much as possible try to take the guesswork out by project-managing your contractor closely.

Don't Live On-Site

This was a simple mistake I made: Don't live in the house during the renovation.

It's too hard, harder than you think it will be. One day you're without water. The next day you're without hot water. The third you might not have a kitchen sink so you're doing dishes in your bathroom.

Even if you like camping, it can be overwhelming at times. We went without our heater for about a month and it regularly reached about 7 degrees centigrade.

It's also agonizingly slow for everyone involved. It feels like an eternity for you because you're living without modern conveniences and it's slower for your contractor/subs as they have to work around you.

- You have to pick which rooms get worked on and which don't. That means your subs can't do the whole house in a go over 2-4 days and instead have to do it in multiple trips.

- You have to tarp and tent all of your things and yet you'll still find dust and debris in your bed, in your clothes, in your dresser, and pretty much everywhere.

The amount of time we spent moving everything around, getting it covered/protected for the work wasn't worth any kind of cost or time savings we might've seen from not having to get a hotel or stay with friends. Compounded by the extra effort it put on the sub-contractors, we really came out behind.

Just move into a storage unit and live somewhere else during the work.

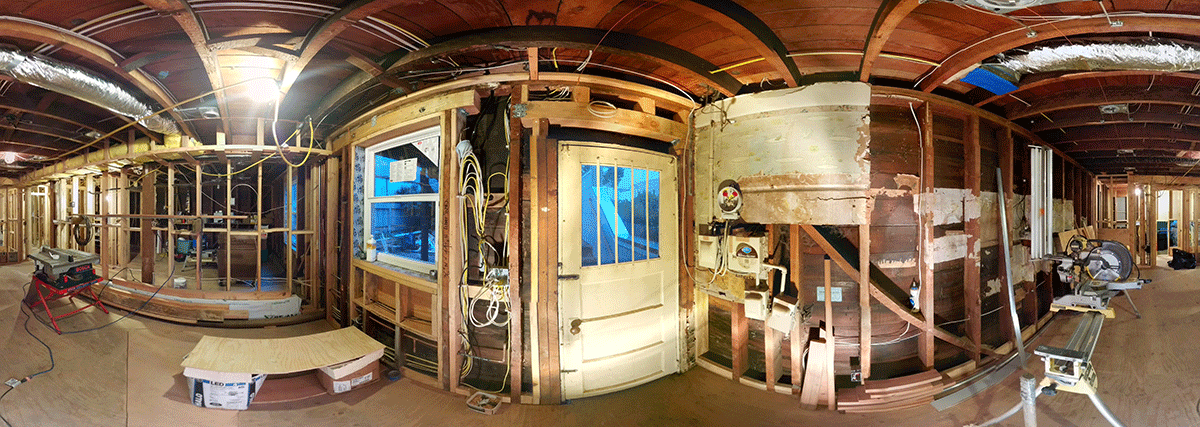

Take Photos Every Time

Whenever you're on site, take comprehensive photographs of the entire property. Yes, the whole thing. Yes, every time. This can be incredibly valuable even if nothing goes wrong.

During work you might see something damaged. With photos, you can prove it was in good shape when it was installed but was later on damaged by someone. Your contrractor will try to tell you it was damaged when they got it and they just didn't notice. You could narrow down the time window to when it happened and and know who's responsible. If there was anyone else on the property, your contractor will try to put it on them. On the positive side, it's really useful to know where everything is inside your walls. The height of your electrical run or where the studs are can be valuable when it comes time to mount some shelving or install a new outlet.

Conclusion

Those are my thoughts about the project overall. Like I said there were many other lessons learned and things I wish I had done differently along the way, but these are the big ones.